Ways we seek permission

Agency and "you can just Do Things!"

Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate,

but that we are powerful beyond measure.

It is our light, not our darkness, that frightens us.

—Marianne Williamson

Have you seen it? The phrase, “you can just do things,” is once again in vogue.

It says: be audacious! Sometimes constraints are chalk lines on the ground rather than concrete walls.

It reminds me of an excellent list of things you’re allowed to do I once read. My personal greatest-hits: outsource your labor (have you considered a personal assistant?), reach out to strangers (both people you just met and famous people!), and ask for more meat at Chipotle (how to do it for free: smile at them and say it with every ounce of kindness you have in you).

I think this phrase is a part of a broader societal conversation about individual agency which has also come into focus recently amidst changing times. Agency is a blend of self-efficacy, determination, and a sense of ownership over one’s path.

I like the car passenger analogy a lot. When we’re a passenger in someone else’s car, we’re bound in behavior by the borders of the permission we have obtained. We ask to lower the volume, or wait for somebody else to ask. If the ride is short enough, we might even just wait for the trip to end. Meanwhile, in our own car, there are no such permissions to seek. We’re free to crank up the A/C, put our feet up on the dash, and blast music as we wish.

These external forces that low agency people find themselves waiting for, are actually just different forms of permission.

I’m defining permission a little abstractly here—a cone of light illuminating the darkness of what previously was known to be impossible, unattainable, or inaccessible.

Seeking permission is the act of negotiating this boundary between do-able, not do-able. It is an intensely personal endeavor, and what I mean by this, is that it is entirely about our perception.

We seek permission from people when we negotiate social, professional, and cultural boundaries. Interestingly, even when we are trying to negotiate boundaries inside of ourselves—what we believe we are, or are capable of, for example—we still are routing through others, or the external world.

I remember the first time I went away from home for a 4 week summer camp, I was incredibly excited because I realized that nobody there knew who I was. And to me, this meant that I could completely reinvent myself: a new stage, a new cast, a new me.

That’s interesting, why did I feel like reinvention was only possible where nobody knew who I was?

This is what low agency looks like applied to one’s sense of self. Their opinion and conception of who I was—introvert, late-bloomer, nerd—held me firmly in place. I was a passenger, waiting for someone else or for a new destination.

In contrast, true agency is internalizing the permission-granting process so that we are liberated from having to seek it from others.

Ways we seek permission

“Once you are ok with people telling you ‘no’, you can ask for whatever you want. Make reality say no to you.”

—Nabeel S. Qureshi

Can we really “seek permission” from reality? Who could grant such heavenly sanction?

Actually, I think this happens all the time. For example, simply seeing someone else do something that we thought was impossible expands the boundaries of our model of reality. This is the Roger Bannister Effect: shortly after Bannister ran the first sub-four-minute mile, many other athletes suddenly broke through the same barrier.

Rather than waiting for someone else to demonstrate that our model is wrong, we can cultivate a sort of skepticism of the world by being curious and asking questions. Be willing to try things, even those that you expect to fail or go badly. By doing so, you escape the trap of confirmation bias and engage directly with counterfactual possibilities—what happens when your expectations are proven wrong.

We can also work to unearth self-limiting beliefs and let them go. The deepest self-limiting belief of all is the scarcity mindset. Conversely, the most expansive world model possible, is believing that the world, and your future, is abundant with opportunities and possibilities, and that you should bias towards exploration rather than exploitation.

“We create our own stress due to our perception of what we must do.”

Roles are the most explicit permissions that we seek. Our professional and social roles dictate what we believe we're "allowed" to do or be. The problem with this is that roles in society are square holes, or round holes, or triangular holes, and humans are more like 4D hypercubes.

I believe that there’s a place for everyone and the first step to finding your unique niche, is to let go of the idea that we must contort ourself into one of these holes that society presents to us.

When the roles we possess (external identity) become imbalanced with our sense of internal identity we feel imposter syndrome. This creates cognitive dissonance where you have been "permitted" by external forces to occupy a space that you haven't given yourself permission to inhabit. You're operating in what feels like "restricted territory" because your internal conception of self has yet to also expand.

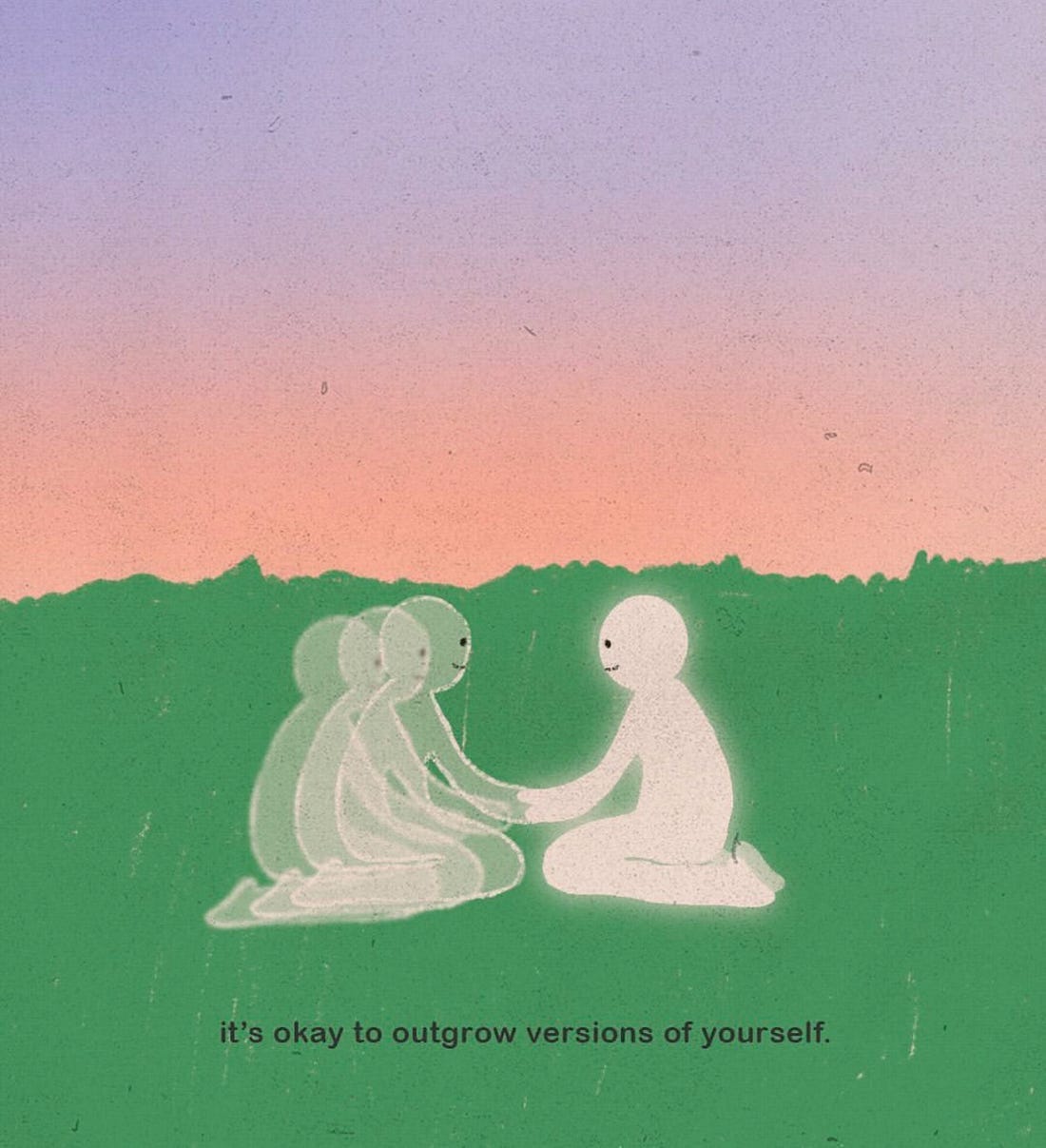

Besides escaping to a place where nobody knows who we are, we can also overcome this by separating what we believe we are from what the world tells us we are. We can do this by striving to accept ourselves with all of our imperfections, cultivating a growth mindset that allows us to expand and “rise to the occasion”, and living in accordance with your values and what they call your “truth”. If you can do these three things, I think that your inner identity will become spacious and flexible, and thus resilient and strong.

“The gods are fallen and all safety gone. And there is one sure thing about the fall of gods: they do not fall a little; they crash and shatter or sink deeply into green muck. It is a tedious job to build them up again; they never quite shine. And the child's world is never quite whole again. It is an aching kind of growing.”

― John Steinbeck, East of Eden

We also seek moral permission, the conception of what is right or wrong for us to do. When we seek moral permission externally, it is usually from religion, spiritual leaders, or figures of authority in our life.

Moral permission is the boundary around our inner sanctity: the set of ethical principles we hold, including abhorrence for disgusting things, actions, and beliefs (and not allowing degradation). Like an internal Overton window, our inner sanctity is a subjective construction.

The process of internalizing moral permission feels especially violent. The first time that I drank alcohol, I felt something crumbling inside me. It was one of the pillars of my inner sanctity—the one that said “good people don’t drink alcohol at this age.” And as it fell, I felt guilt and shame and wondered if I was no longer the same person as before this shattering.

But, like a forest fire, sometimes destruction precedes creation. Eventually, I erected a taller, stronger pillar in its place which said “my inherent goodness is independent of others’ approval.”

What about the permission to be ourselves authentically, or to change who we are?

To me, seeking the permission to be authentic sounds like a whispered question: you won’t judge me negatively for this right? It’s driven by fear of rejection and the fundamental need for acceptance.

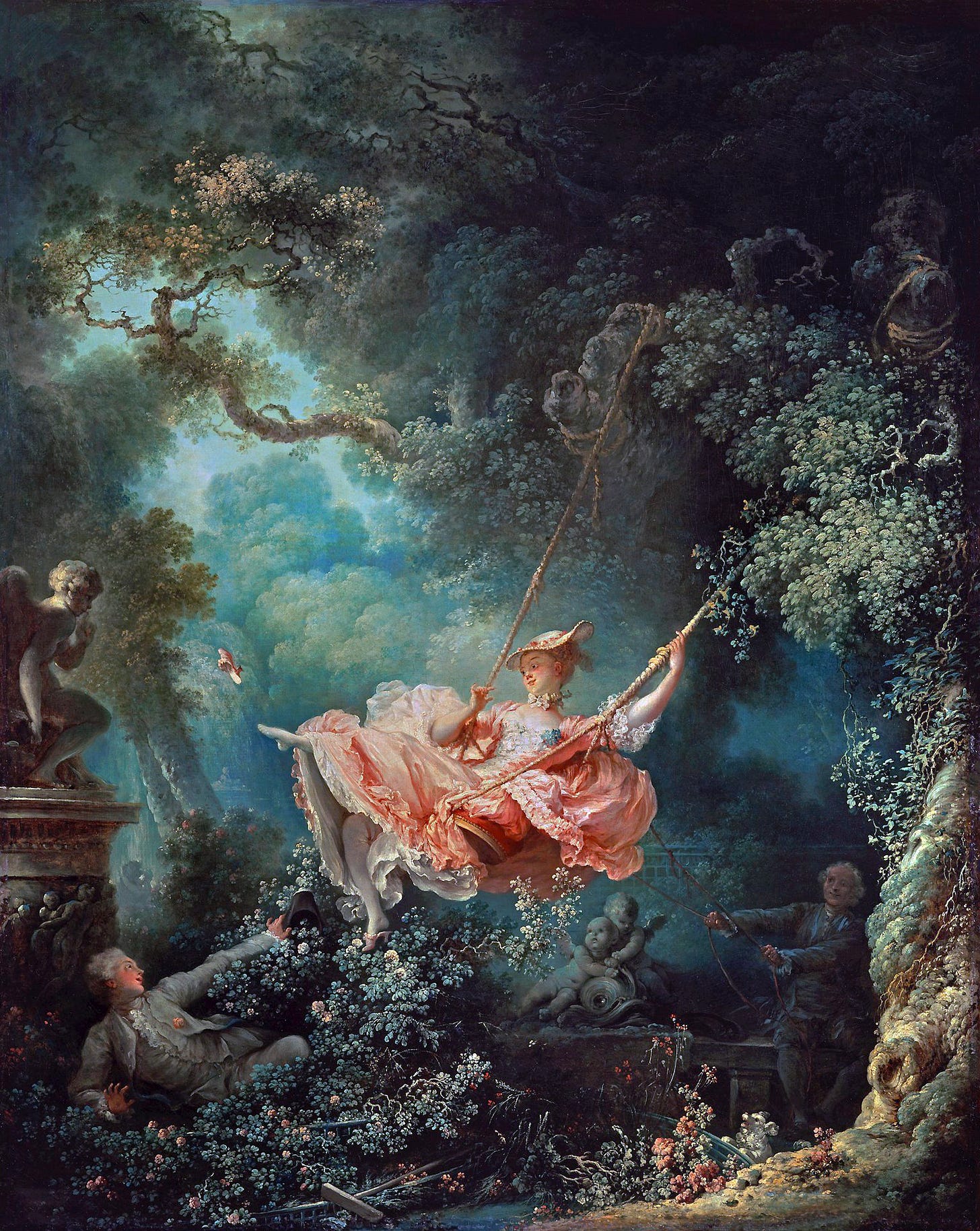

When I was visiting Berlin this winter, I discovered that my trip had aligned with the start of the Berlinale, one of the Big Five film festivals in the world. Excitedly, I bought tickets and went to see one of the showings. When the movie ended two and a half hours later (it was, to my dismay, entirely in German. Still, great visuals, 8/10), the credits rolled and the theater was silent. I wasn’t sure if it was customary to clap at the end of an official showing, so my hands stayed hovering in the air while I glanced around. Then, one person began clapping somewhere to my left, and like an avalanche, the applause began.

Why didn’t I begin clapping myself? It would have been more true to myself—I believe in clapping to show my appreciation for a good film. Instead, I waited and sought that permission from someone else, a valiant First Clapper.

When we seek this permission to be ourselves from other people, the thrill of feeling accepted, of recognition, of admiration, are like gusts of wind that lift you sky high for a precious, fleeting moment before you plummet back down. It always fades in the end, leaking through your desperately cupped hands.

When it comes from someone else, the world is not enough to etch these beliefs in your heart to stay. Who can give you that permission in any enduring, timeless way except you yourself? I know that life is stifling and gray when I find myself seeking from others the permission to be myself.

Instead, now I try to internalize that permission by believing that I am enough as I am, overcoming shame through self-compassion, and getting to know my authentic voice.

Inner permission is freedom

“Surround yourself with people who are free in ways you’re not.”

—Venkatesh Rao

Call me dramatic, but clearly, along the axis of self-consciousness, First Clapper possessed more degree of freedom than I did.

Surrounding yourself with First Clappers, people who are internally permissive and liberated in ways you’re not, will slowly allow you to begin to absorb the quality of lightness, of inner spaciousness, of freedom that they emit. I believe our inner permissiveness diffuses into those who spend time with us and are open to receiving it.

Good leaders, in my opinion, are First Clappers. They grant permission by precedence, for example, by publicly acknowledging their own mistakes and clearing the way for a culture of nonjudgmental accountability.

A lot of people aspire to be this kind of leader through emulation or by reading prescriptive books like “48 Laws of Power”, "Radical Candor", or "Extreme Ownership". Not that these books don’t contain valuable information, I just think that there is another way besides memorizing rules and pattern matching to situations, which is simply to be internally freed yourself. The way to do this is through internalizing permission in all the ways discussed above.

Finally, while we’d all love to be mythical 10x agentic, ubermensches, leaping around from rooftop to rooftop, first, I think we can all aspire to be First Clappers.

For myself, next time, I hope to be the First Clapper for my fellow theater-goers, and for my friends, family, coworkers, employees, and, someday, my children.

And, as we let our own light shine,

we consciously give other people permission to do the same.

As we are liberated from our fear,

our presence automatically liberates others.

—Marianne Williamson

I loved all your visualizations!!

And a shoutout and celebration for first clappers! You guys are the real ones

A related phrase I've seen a lot lately is "be cringe!", and I think it ties back to the same idea of how we are often negotiating boundaries not only with our environment but also with ourselves. The First Clapper was not afraid to be cringe, we shouldn't be either.