Lessons for First Time Consumer Founders

from founding a YC consumer startup

This is a collection of advice for first-time consumer founders. During the two years I spent building Shortbread, I read a lot of books, essays and frameworks and had the chance to talk to many successful founders. I’ve distilled it to a short list of what I think would be the most useful to a first time founder building a consumer product.

1. Distribution

Distribution should be baked into your business. Brian Balfour’s four fits model: product–market fit, product–channel fit, channel–model fit, and model–market fit, is a very useful way of thinking about it. It’s not enough to make something people want—you also need to design it so that it moves through the right channels, with the right economics, to reach the right market.

For consumer companies it comes down to the unit economics of your business, meaning the revenue and costs associated with a single customer.

Growth is a balancing act between CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost), retention, and LTV (Lifetime Value). For the business to be sustainable, the amount you make from a customer (LTV) must be greater than what you spent to acquire them (CAC). The payback period, how long it takes you to earn this LTV, matters too in limiting your growth rate.

Make sure you know your ideal user persona and where they tend to gather (online and offline), so you’re not wasting time distributing to people who will never care.

Beware chasing viral spikes. As with all top-of-funnel strategies and tactics, if the product is bad and users churn somewhere downstream then you’re just filling a leaky bucket.

A more consistent strategy is to build growth loops into your product, where each new user creates the conditions for more users to join (it’s common to hear K-factor come up here; this was a useful concept when referrals were a dominant growth engineering tactic but not so anymore).

Common growth loop mechanisms include social sharing, content creation, marketplace dynamics, community participation, or other network effects, but the key is repeatability and compounding.

Pinterest is a classic example: Users sign up and 'pin' content to boards which are indexed by Google Images, leading other users to find this content via search or social, sign up to create their own board, and the loop repeats.

Distribution should be founder-led (doing things that don’t scale, an old YC maxim): emailing early users yourself, pitching the first sales calls, showing up in forums, writing the first blog posts. This is vital, because it’s the tightest feedback loop for learning what works and what doesn’t. If you can’t personally get distribution working, it’s unlikely a hired marketer or salesperson will fix it later.

“Distribution is essential to the design of the product. If you invent something but you haven't invented an effective way to sell it, you have a bad business. Superior distribution by itself can create a monopoly, even with no product differentiation. The converse is not true.” —Peter Thiel

2. Talk to users before you build

This is to help you know what problems are valuable to build solutions to, so that you don’t build solutions looking for a problem. “If you build it they will come” is often dunked on for good reason, but, as they say, there is not much signal in the rejection.

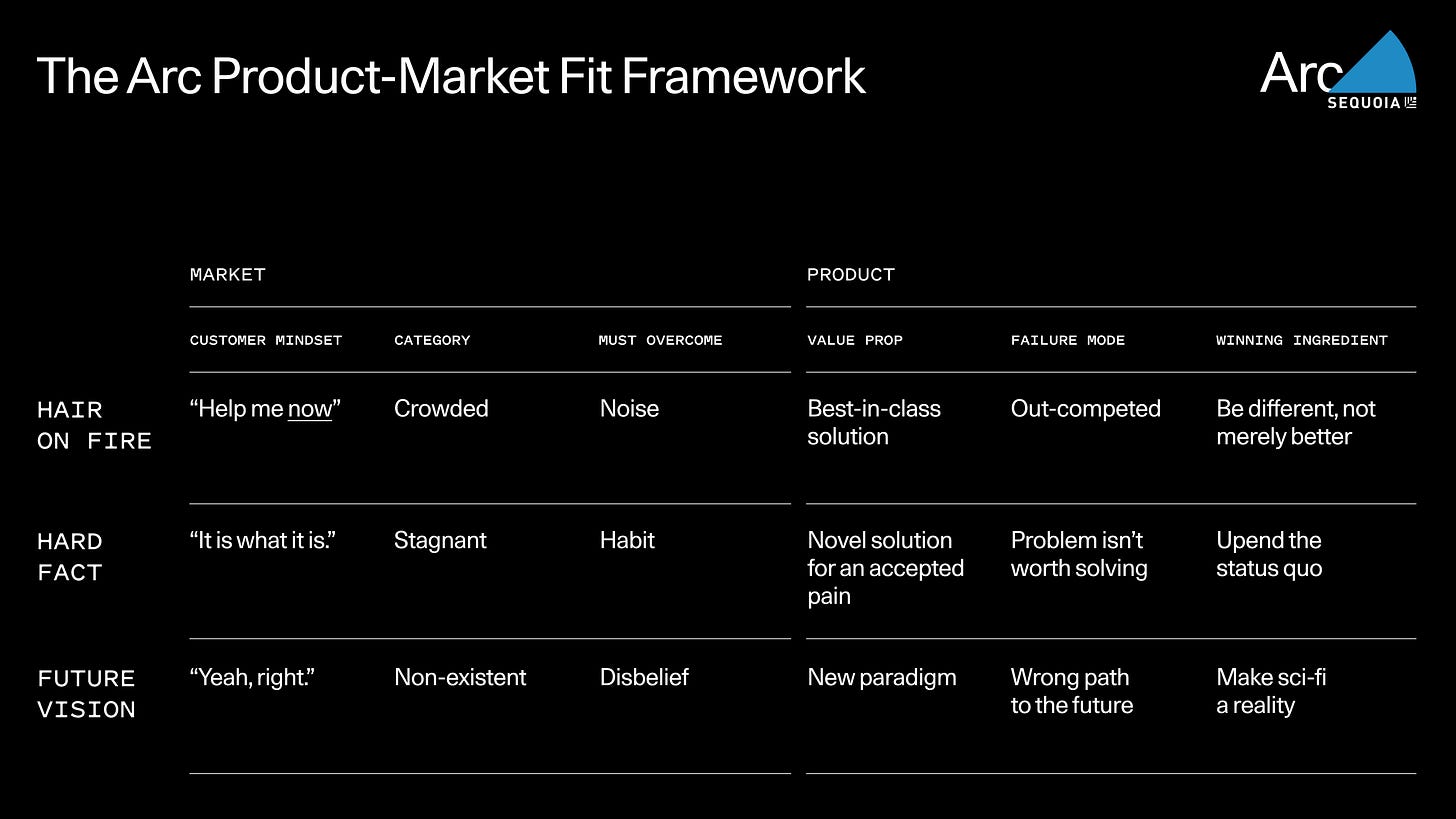

A framework from Sequoia that I find interesting and useful states that for a product to find product-market fit it must ultimately overcome noise, habit, or disbelief:

Alternatively, two common ways to fail are building something that customers do not want, and overestimating the size of a market. Both of these are solved through talking to users; your goal is to understand the domain and the problem space deeply, as if you were immersed in their world and seeing through their eyes.

More specifically to building consumer products, success requires deep insight into the psychology of the individuals in your market, as opposed to the businesses. This is why a good starting place is to solve a problem that you personally encounter and understand intimately.

How to talk to users: follow 3 principles from The Mom Test.

Lead with their problem, not your solution. Avoiding mentioning your idea gives you the chance to learn about their world first.

Ask about specifics in the past instead of generics or opinions about the future.

Feature requests should be understood, but not obeyed.

When you build and begin iterating, start small; you get more signal from ten people who love or hate your product than a thousand who kind of like it. Build the simplest thing that could solve their problem and launch earlier than you want to, so you can challenge and validate your assumptions by having your solution in the hands of real users. You can launch multiple times, that one big launch is fool’s gold.

As in life, your goal should be to maximize rate of learning; since you, as a startup, are default dead and dying, everything rests on you learning enough before you run out of time. The way to maximize this is to run cheaper experiments, more often, and with reliable feedback loops.

3. Retention before growth

Unless you're building a lifestyle business with a product designed for churn (many AI consumer apps are like this, especially the ones that go viral on X for successfully using a guerrilla TikTok marketing strategy), you should just focus on building a product that retains users. There's a million tactics, playbooks, and hacks to try to be seen as valuable, but at the end of the day, there’s no hack to actually being valuable and therefore retaining users.

To that end, beware putting the cart before the horse: spending too much time developing a “personal brand”, chasing virality via TikTok ramps / the vaunted Product Launch of the day, premature scaling, paid marketing.

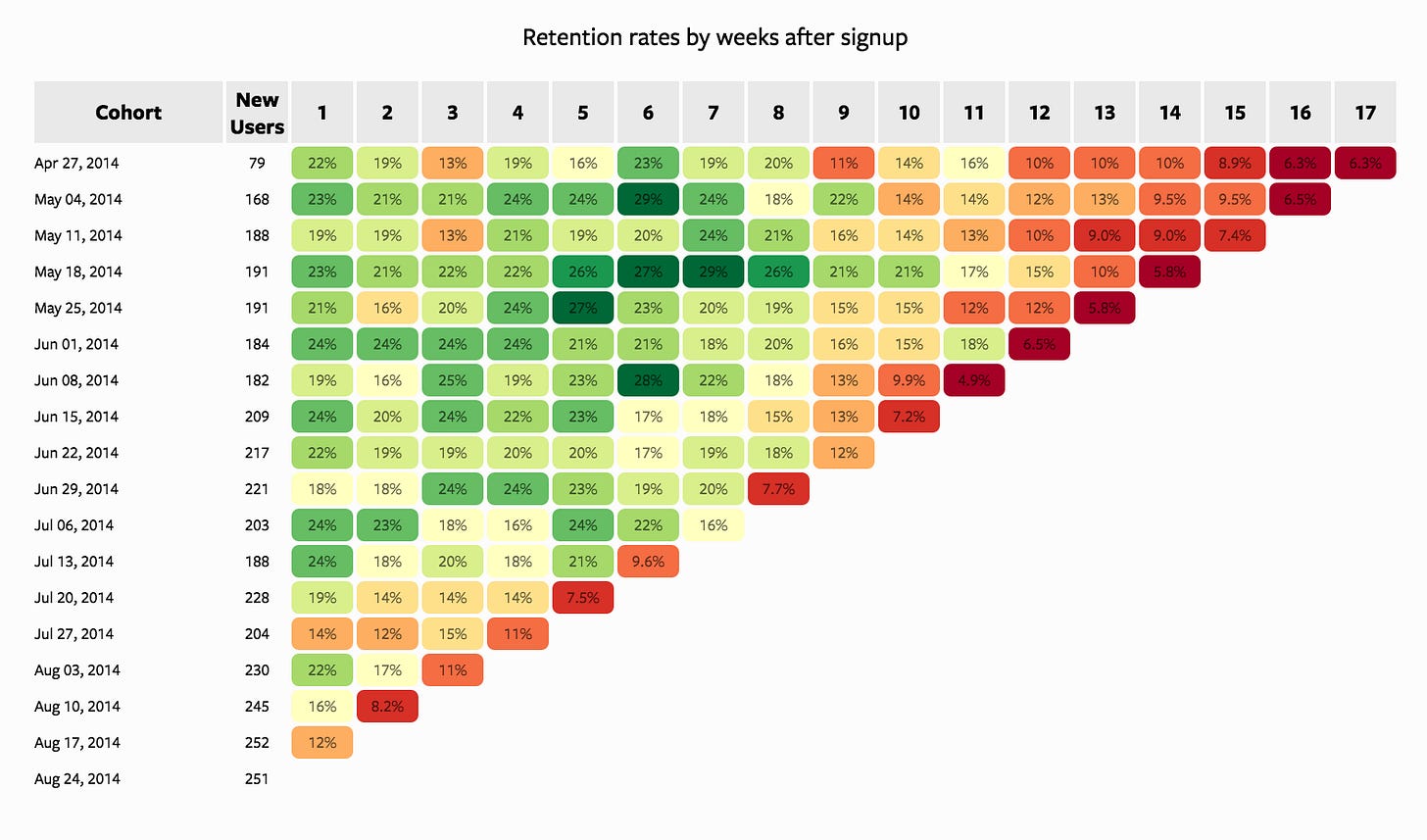

To measure retention, build a cohort retention chart. They look like this:

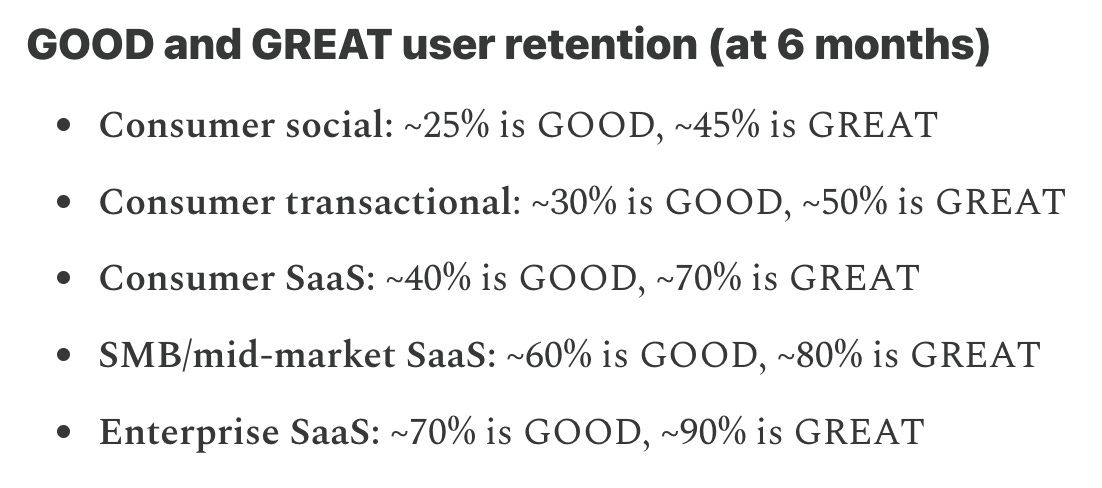

At the very least you need to have a flattening retention curve; it’s hard to build a business that eventually loses every user that’s acquired. Even better, you should research the benchmark retention of top performing products in your category. For a generic overview:

These numbers are incredibly high, but are telling of how strong the value and stickiness of the top percentile products (Facebook, Amazon, Spotify, Instagram, Notion…) are. Your early stage product won’t start out with retention this strong, but it shouldn’t be too low either (unless your CAC is super low, e.g. mostly organic growth)—significantly improving long-term retention is notoriously difficult.

This is because good retention is hard. As Marc Andreessen once said, your customers’ (screen) time is already all allocated. While you may be in a niche category, in a sense, you’re competing with the entire attention economy.

The 2 things you can do with the best chance of improving retention are:

Improve your product—optimize the UX, make it cheaper, increase top feature adoption, solve more problems

Bend the curve earlier by optimizing for activation—the magic “aha” moment of your product, when value is delivered to the user

4. A startup is a war with 1000 fronts

You can't win all of the battles, you can't even attend to most of them; fortunately, a few matter much more than the rest. As with most things in life, assume a power distribution and try to be focused on the one most important thing, the 20% that will create 80% of the results.

Sometimes, you might not be able to see the most important thing because you're too focused on lower level optimizations: A/B testing landing pages and pricing options, running experiments on trial duration to improve conversion, and building the slickest personalized onboarding, when the highest leverage problem right now is fixing D30 user retention.

My recommendation here is basic: identify the key metrics you really care about and set aside regular time to align with your co-founder on high-level strategy based on the data. You should have a notion of the altitude at which you’re operating, and intentionally ascend and descend to regularly assess priorities. No detail should be beneath you; in my opinion, this is one of the most important things a founder needs to do, maintaining massive context across the surface area of the startup, up and down the organizational/technological/strategical stack. This is what the founder mode discourse was about.

More generally, this also means you should say be saying no a lot. Some common traps you should be rejecting: perfectionism / over-engineering, shiny but non-essential product features, caring about vanity metrics, attending vacuous networking events or idle VC coffee chats, hiring too early, premature scaling, and over-indexing on paid marketing before retention / PMF (product–market fit) is there.

“People think focus means saying yes to the thing you’ve got to focus on. But that’s not what it means at all. It means saying no to the hundred other good ideas that there are. You have to pick carefully. I’m actually as proud of the things we haven’t done as the things I have done. Innovation is saying no to 1,000 things.” — Steve Jobs.

5. Hire the right people

This is the highest leverage thing you can do as a founder, starting with your cofounder.

Don’t settle; you wouldn’t for deciding your life partner, resist doing so here as well. Cofounder relationships are like marriages. Like divorces, founder break ups are more common than you probably think and can get almost as messy; better to be solo than to find yourself entangled with a bad cofounder.

For all the time you’ll be spending working together in such close capacity, you may as well be temporary life partners. This is why both your professional compatibility and your compatibility as people matters a lot, and also why YC looks for founding teams that have known each other a long time. Do you like this person? Can you see yourself working with them around the clock, every day, for the next 4+ years? Do you trust them? Is this someone you’d want by your side when things are hard and your back is against the wall?

To Paul Graham the most important attribute is to be relentlessly resourceful.

“There are a bunch of useful qualities in founders, but I’ve narrowed it down to the 3 most important: determination, domain expertise, and ability to sell. At least one of you is going to have to sell.”

—Jessica Livingston

For your first employees, the same applies—don’t settle, and don’t justify settling because you feel the pressure to scale up your team. Hire slowly, fire quickly. Have high standards.

The 10x engineer cliché is trite but true: it's exceedingly rare to find an engineer who is strong or has aptitude for product, business, technology, and design, but a 4/4 is the unicorn that you should be searching for. They should be someone smart, hard-working, growth-oriented, agentic, and cares about their work.

Most likely, you won't find these people in your inbound. Look for them in your network, in strongly-filtered high-signal communities, and by cold-reaching out to them personally online.

6. Learn from others

Copy what works. You probably don’t need to innovate a unique Go To Market strategy — meaning how you get your initial customers and how you charge them. Research and copy the initial GTM strategy of successful companies similar to yours. The added benefit is that you will appear familiar to customers rather than radical.

A horde of founders before you have failed and succeeded in building technology startups in every domain and industry. Study their stories so that you may potentially avoid their mistakes or replicate their successes. Look for them on founder blogs, company postmortems, podcast and interview appearances, essays, VC blogs.

Even better, cold email them, follow up, offer to buy them coffee/lunch while you ask them questions to learn about their founding experience and listen for advice. When I was in Berlin at one point, my cofounder and I visited Ali Albazaz, CEO of Inkitt, at their office to ask questions about their early days. Despite us both operating in the same space, he was generous with his advice, and we learned a lot about successful strategies they employed.

At the same time, know that every start up is different and that the invisible details may be the crucial difference between one company's success and your flop, or vice versa. Don't average your advice, and be diligent in evaluating what you hear.

Lastly, don’t blindly fear competition — startups tend to die of suicide not murder. Unless you are in a truly winner-takes-all market, other startups working on your idea should give you some validation on the potential for product market fit. HubSpot built a $25B business in the face of Salesforce’s $250B one, amidst hundreds of others in the overcrowded SaaS landscape. Good ideas are cheap, execution is everything.

“A good startup idea in someone’s brain is usually a 1mm head start at the beginning of a marathon.”

— Garry Tan.

7. Timing is critical

There are lots of fun analogies here. In a fast-moving river, it hardly matters whether you’re riding a log or a fiberglass kayak—you’ll be carried downstream all the same. Experienced surfers know to wait for the right wave to catch.

So too, with technological waves: they move in long S-curves that unfold over years, with different paths to success depending on whether you’re in the start, middle, or end of the curve. The right timing doesn’t guarantee success—but the wrong timing almost guarantees failure.

“The #1 killer of startups is lack of market.” In a great market, “the market pulls product out of the startup.”

—Marc Andreessen

This is the story of a lot of the biggest internet era companies. Reed Hastings pivoted Netflix to streaming as broadband and connected TVs crossed the threshold; YouTube rode cheap digital cameras, Flash, and rising home bandwidth to unlock UGC video; Instagram was native to the iPhone 4 era and took a winning bet on the fact that everyone would soon have a great camera in their pockets, capable of uploading images to the internet.

As these waves appear, crash, and fade, so too do markets emerge, expand, and eventually shrink. My point is, of all the ways a startup can be “lucky,” the most decisive is being on the right side of the times. Unlike most forms of luck, this one is directly in your control—choose the right wave to ride.

Form a thesis about where the times are headed, meaning what technological developments are happening, and how industries are currently or will be disrupted in reaction, based on research and talking to users. Figure out what is your differentiated proposition, how will you distribute it, and why are you and your cofounder(s) poised to execute successfully.

Now you have the foundation of your pitch when you go to court the investors in their silly game.